I created an AI that beats me at tic-tac-toe

February 25, 2018

Feel free to go lose in tic-tac-toe here.

Shamelessly taken from Wikipedia.

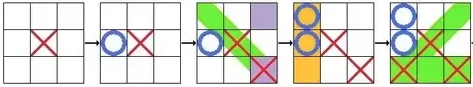

When I was in first grade, I thought of myself as the best tic-tac-toe player in the world. I beat my friend who had taught me how to play just moments before. Unfortunately for me, that feeling of genius didn’t last very long. My dear friend, whose name I can no longer remember, started dishing out pincer attacks. The games started looking something like:

Yeah. Sucks for O.

I was devastated. I went home and practiced until I could see those tricks coming from a mile away. It didn’t occur to me then that I was actually searching through a game tree to see if the move that I was making would lead to a favorable outcome or not.

You: So… what is a game tree?

Me: Oh. It’s just the state space of a game where each node is a state of the game and each edge is a valid move.

You: …

Me: Sorry. A state space is the set of states reachable from the initial state by any sequence of actions. At least that is how Russell and Norvig define it. The initial state of any game is the state of the board at the start of the game. The initial state for tic-tac-toe would just be a 3 by 3 grid with no X’s or O’s in it. Then whenever a player makes a move the game moves to a new state. For example, the image above where O loses shows 5 states. After each move is made, a new state is reached. The collection of all reachable states is the state space. Any state that requires breaking the rules of the game to reach is not considered a reachable state. Thus a tic-tac-toe board with two X marks and no O marks is not a reachable state.

Not a valid state.

You: How does this relate to you creating an AI that beats you in tic-tac-toe?

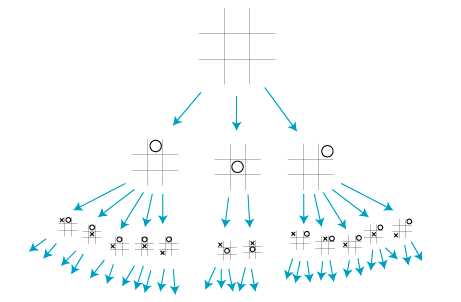

Me: That’s easy. I just made the computer simulate all of the possible outcomes of each available move at the beginning of each turn. When it is done with the simulations, it chooses the move that leads to the best outcome. This is equivalent to searching through the game tree for the leaf that has the state with the best possible outcome.

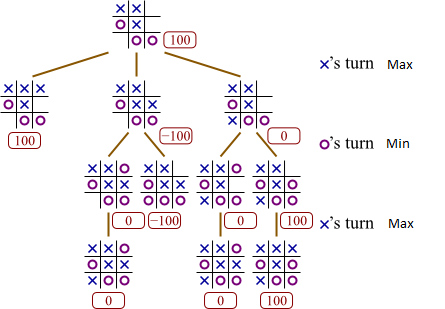

Partial game tree for tic-tac-toe. Credits to Professor Eppstein of UC Irvine.

A natural question that arises is whether this is feasible in terms of cost. We can perform back of the envelope calculations to see that there are not that many states. Suppose that the computer goes first. Then there are 9 possible moves. For any of the 9 moves that it chooses, it must simulate where the other player will move in response to that. There are 8 possible choices for that. Then it switches back to the computer to move again with 7 choices left. This goes on until there are no moves left. Thus on the first move, the computer needs to look through 9! = 362,880 states. On the computer’s next move, there are 7 possible places left to mark so the computer needs to look through 7! =5,040 states. If we assume that the game lasts until there is only one possible move left for the computer, then the computer needs to look through 9! + 7! + 5! + 3! + 1! = 368,047 total states. For comparison, the chess game tree has about 10¹⁵⁴ nodes.

Now that we know that we can just look at the game tree to find the best possible move and that it is feasible to search the game tree, what algorithm would work best here? The minimax algorithm seemed like a natural candidate.

In any turn based two-player zero-sum game, you are always trying to reach the best possible outcome for you which in most cases is winning. This is equivalent to the other player reaching the worst possible outcome. Similarly, if the other player reaches the best possible outcome for herself, this is the worst possible outcome for you since you lose. Thus if we let U:State → ℝ be the utility function then your goal would be to maximize the utility that you get at the end of the game while your opponents goal would be to minimize your utility by maximizing hers.

Assuming we are dealing with a rational opponent, the minimax algorithm bubbles up to the top the maximum possible utility of each move for the given player’s turn.

For a clearer explanation of what the minimax algorithm is doing, take a look at the image above. Suppose that winning gives us a utility of 100, that losing gives us a utility of -100 and that a tie gives us 0 utility. We could play the top right corner and win giving us a utility of 100 but lets consider the other two cases as a thought exercise.

Suppose that we choose the open position in the middle row. Then when it is O’s turn, since we are assuming that it is a rational opponent, O will choose to play the position that minimizes our utility. If O plays the top right corner, our utility is 0 and if O plays the bottom left corner then O wins so our utility is -100. Thus we know that O will play the bottom left corner so we know that if we play the middle row then our utility will be -100.

Similarly, if instead of playing the middle row we played the bottom left corner instead of the middle row then O will have two moves to choose from. If O plays the middle row then we can win by playing the last open spot. O does not want this. O sees that if she plays the the top right corner instead then it is a tie so we get a utility of 0. Since this minimizes our utility, O will play the top right corner instead. Hence if we play the bottom left corner then we know that the game will end up as a tie and we will get a utility of 0.

It is clear from this analysis that of the three moves, playing the top right corner will give us the most utility. Thus, as a rational agent, that is the move that we choose to play.

Let UTILITY(state) return the utility of the current state. Let ACTIONS(state) be a list of all the valid moves in the current state. Let RESULT(state, action) be the resulting state after making a given action in the current state. Then the minimax algorithm is given by

MINIMAX(s)

For every a ∊ Actions(s)

if MIN-VALUE(RESULT(s, a)) > UTILITY(RESULT(s, best))

best = a

return best

MIN-VALUE(s)

If GAME-OVER(s)

return UTILITY(s)

For every a ∊ Actions(s)

sim-utility = MAX-VALUE(RESULT(s, a))

if sim-utility < worst

worst = sim-utility

return worst

MAX-VALUE(s)

If GAME-OVER(s)

return UTILITY(s)

For every a ∊ Actions(s)

sim-utility = MIN-VALUE(RESULT(s, a))

if sim-utility > best

best = sim-utility

return best

To see a version of this algorithm in JavaScript, click here.

MINIMAX is very clearly an application of depth-first search. It has a running time of $O(b^n)$ where $b$ is the maximum number of valid moves in a given turn and $n$ is the maximum depth of the tree.

This all assumes that we are playing against a rational opponent. What if the opponent played sub-optimally? It isn’t too hard to see that MINIMAX cannot do worse in that case since the opponent will have made a move that does not bring us to a state where we have the minimum possible utility.

The astute reader will realize that this algorithm does not create an AI that always wins. It does however create an unbeatable tic-tac-toe computer player. That is, at best you will be able to tie. If like me, you are making your moves too quickly, you may even lose.

Feel free to go lose in tic-tac-toe here.

Disclaimer: If you claim to have beat it, don’t be afraid to list the moves you made to win in the comments below. The computer will make the same move every time so we can verify that you are indeed a tic-tac-toe grand master. By teaching us how to beat it you will also be providing a great service to human kind.